By Jessica Leff

Humans love to find patterns and categorize things, and they tend to sort the things that they care about. So, it is understandable that people find many ways to classify each other. For years, one method has been categorizing individuals as either right-brained or left-brained. Right-brained people are creative and emotional while left-brained people are logical and quantitative. But, a recent study found out that this organizational structure is nothing but a myth: there is no anatomical evidence of “sidedness.” Instead, it’s nothing more than a figure of speech, an artificial social category.

And Wyss Technology Development Fellow Angelo Mao, Ph.D. proves this. Mao has always been interested in science and writing poetry, choosing to attend Harvard University for his undergraduate degree instead of a more technical school because Harvard offers strong science and humanities programs. He explains, “It’s sort of a misconception that you have two completely different ways of thinking. The stereotype is that science is super logical, and poetry and the arts are super creative, but it’s a lot more complicated than that.”

Mao went on to earn his Ph.D. in the lab of Core Faculty member David Mooney, Ph.D., where he worked on a single-cell encapsulation technology for improved cell therapies. He now works with Core Faculty member Jim Collins, Ph.D., on various synthetic biology projects. With Collins and colleagues from the lab, he recently authored a publication on eToeholds, an engineered control element that could make RNA therapeutics safe, cell therapies more effective, and enable novel forms of biodetection.

Creativity in Science and Engineering

As Mao points out, the line between science and art is not so clear cut. Researchers use creativity when designing experiments. Scientists and engineers find creative ways to build their technologies. Throughout the technology development process, researchers must embrace the unexpected and respond in inventive ways. If they do not get the results they expected, they must develop a new project or find a novel direction. Mao says, “If you don’t have an open mind, if you can’t think outside the box and conceive of numerous possibilities, then it will be hard to figure out what’s truly happening in your experiment if it doesn’t go as planned.”

It goes the other way around too. Visual artists, like painters and sculptors, are like engineers in that they must find out how to create a physical piece. Another Wyss artist, painter and Postdoctoral Fellow, Dionis Minev, Ph.D., explains, “I think the creative design process involved in my scientific work is directly related to the creative process used to make art. That’s probably why I love both so much.”

Writing a poem is like constructing with words. It presents a problem to solve. The poet must figure out the best way to express their feelings, observations, or messages with the tools they have. Like an engineer, a poet solves the puzzle and finds out how to put different pieces together and use different tools to solve the problem.

Science as Art

Science can be stunning in and of itself. In 2019, the Wyss held a photo contest to celebrate the beauty of science and the winning images are on display in our space. Wyss Institute technologies have also been featured in exhibits at art and design museums such as Cooper Hewitt, MoMA, and the Barbican Centre.

The stereotype is that science is super logical, and poetry and the arts are super creative, but it’s a lot more complicated than that.

Science Inspires Art

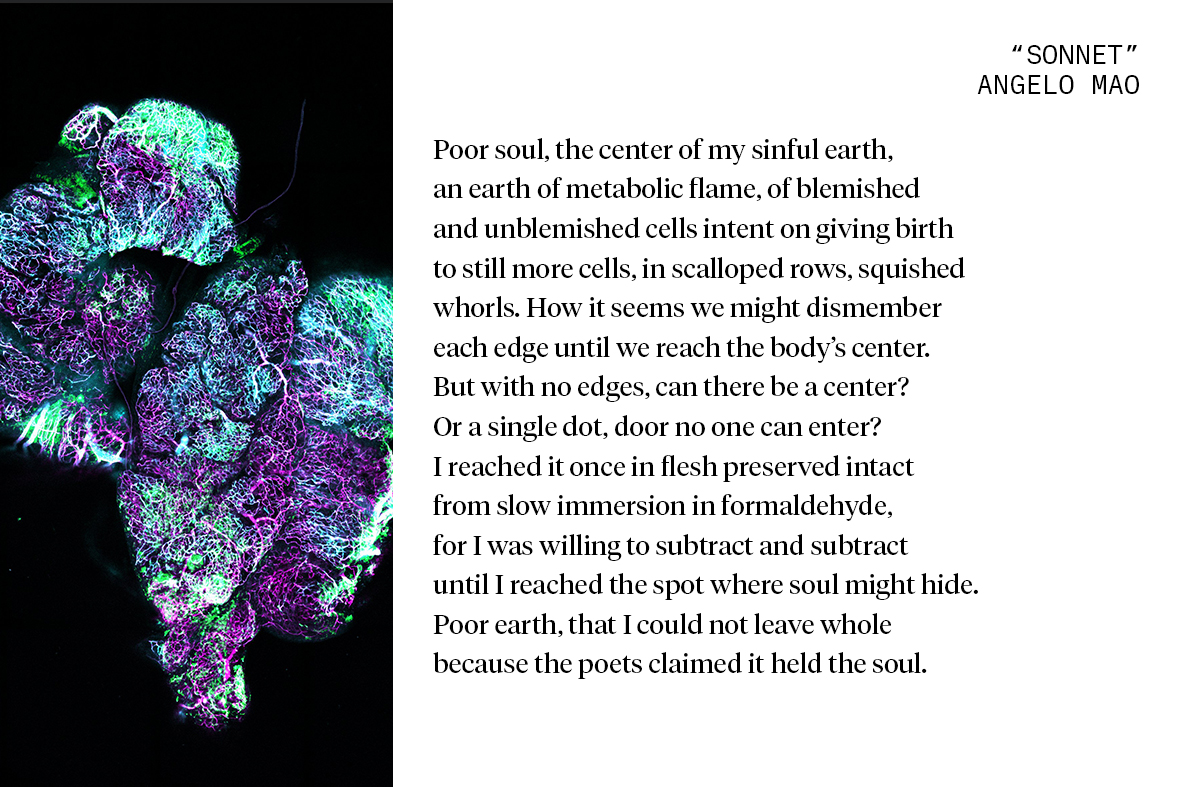

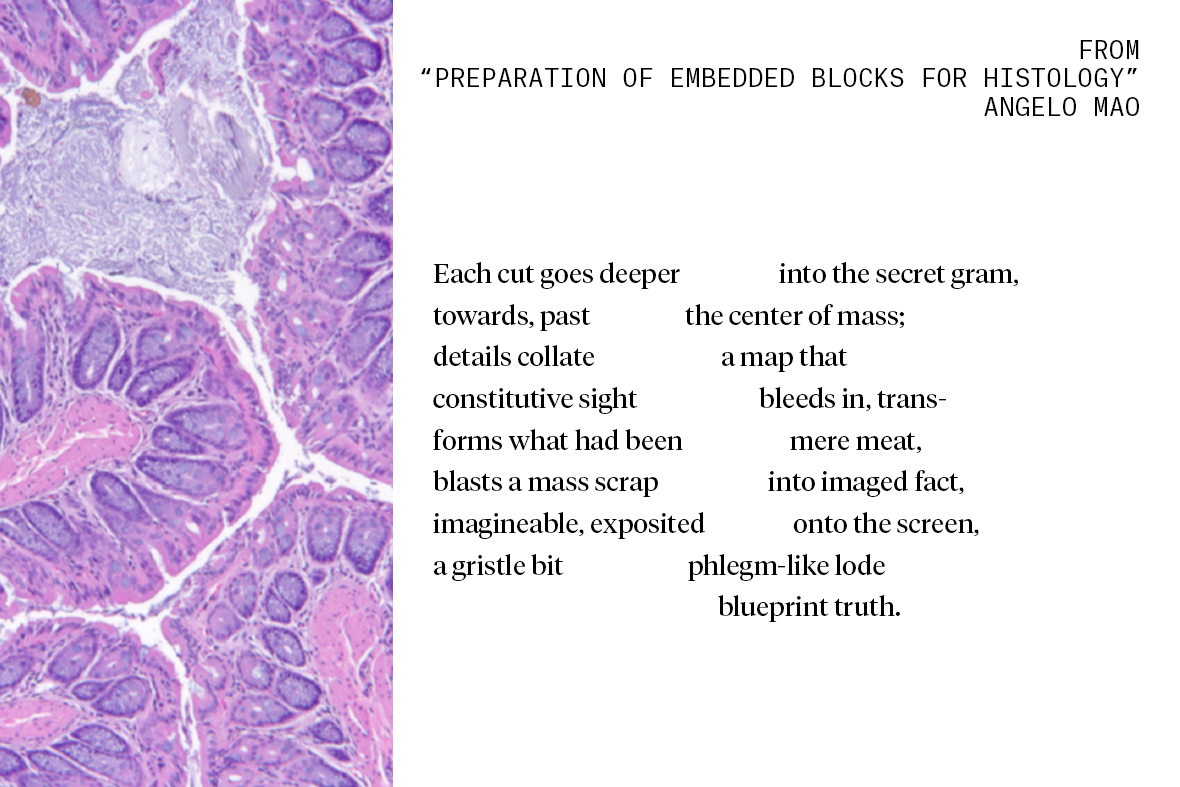

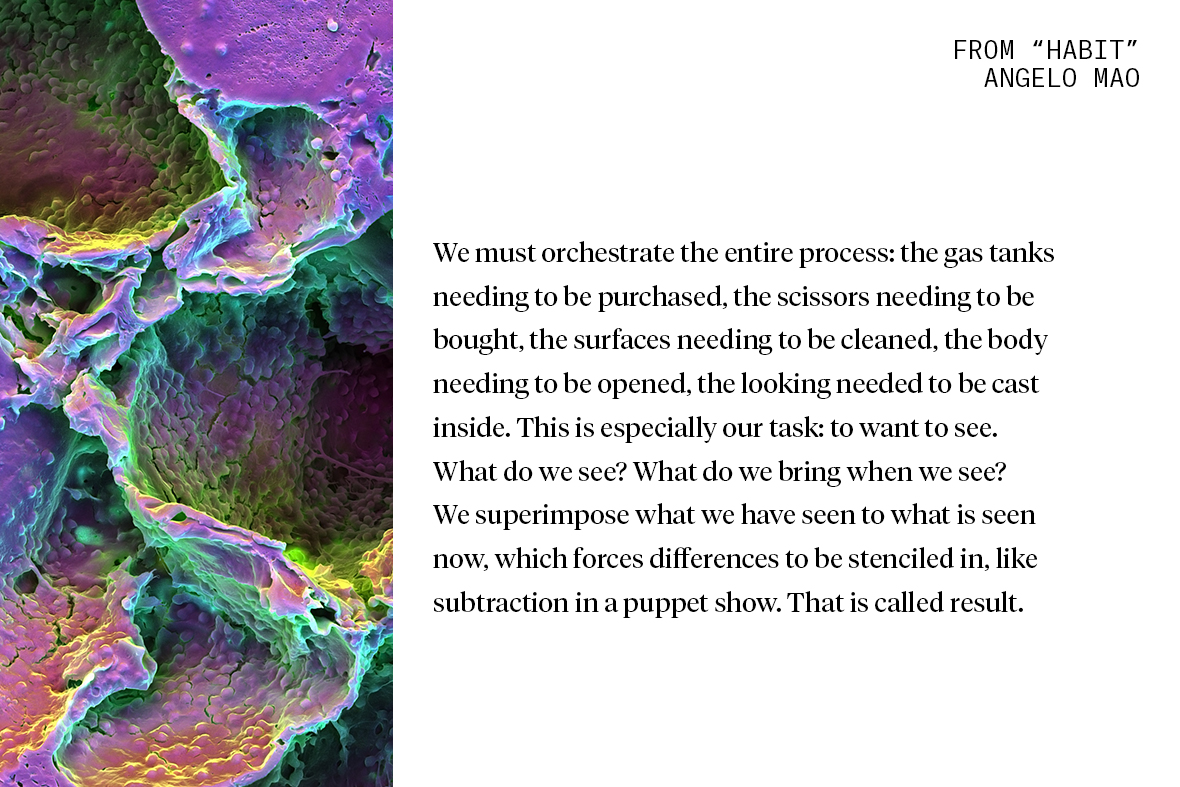

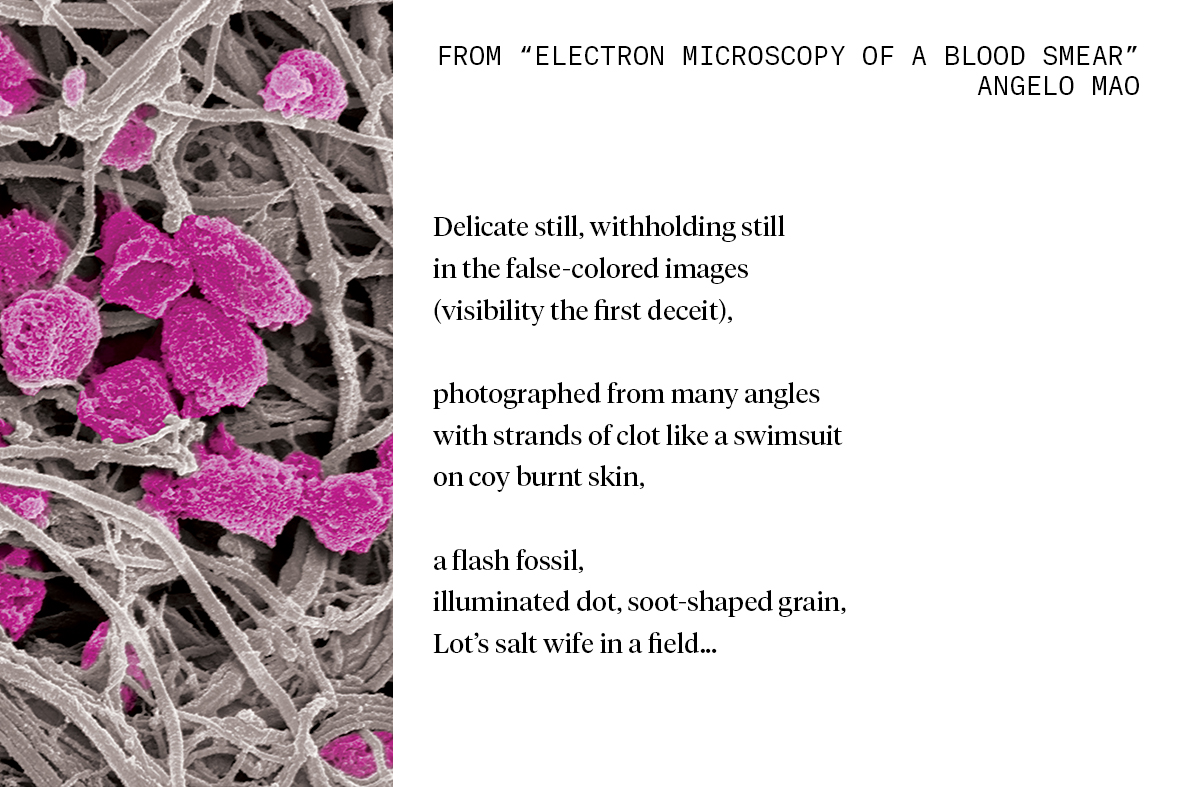

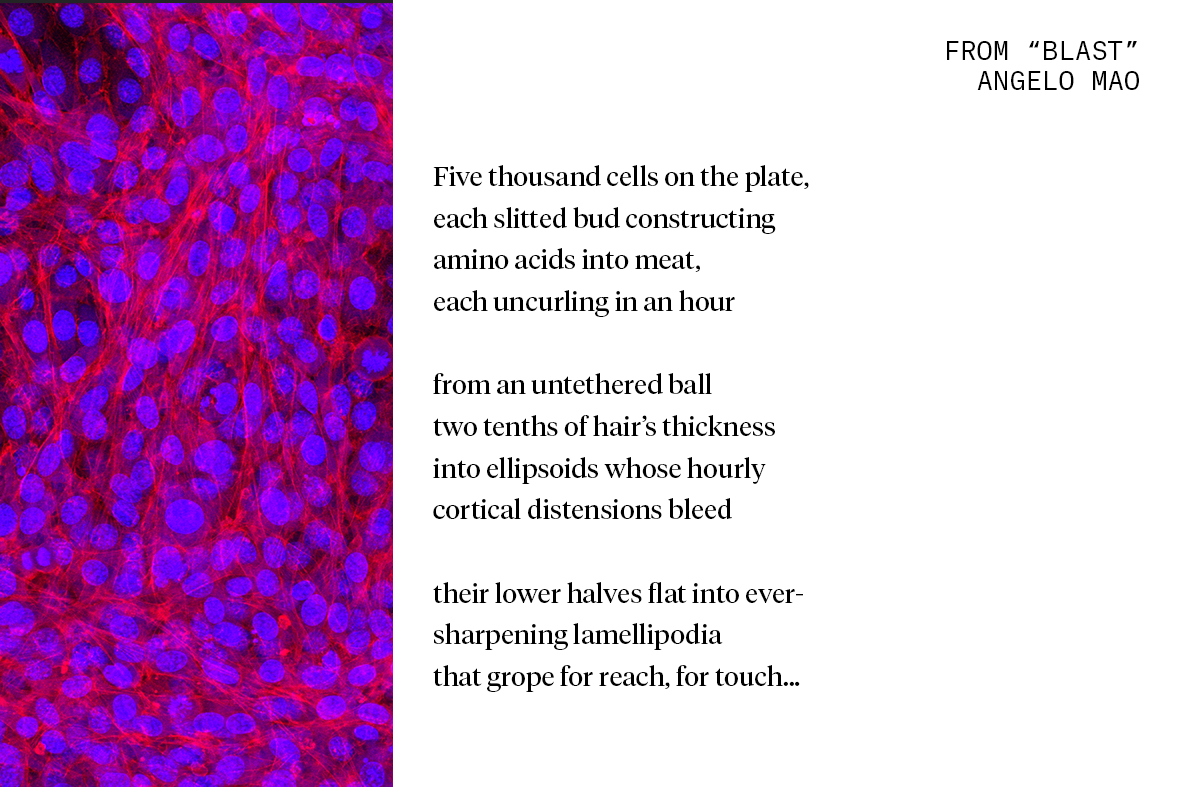

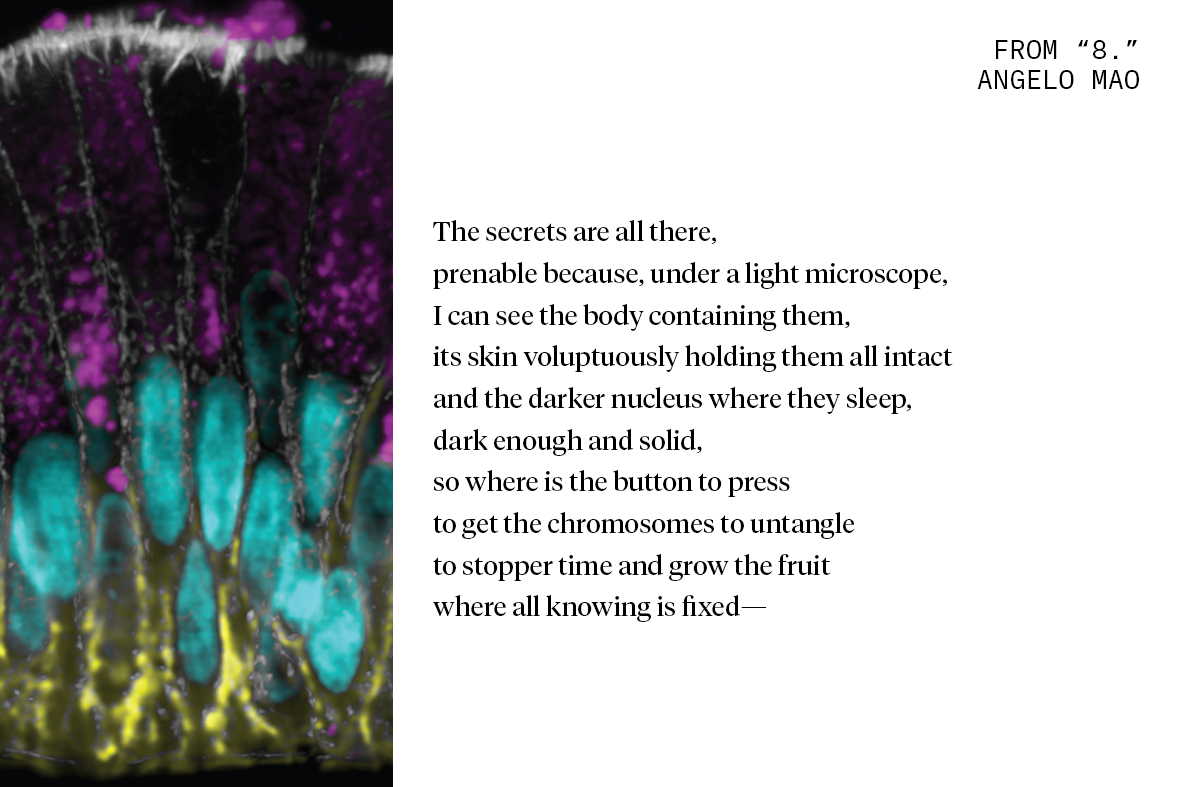

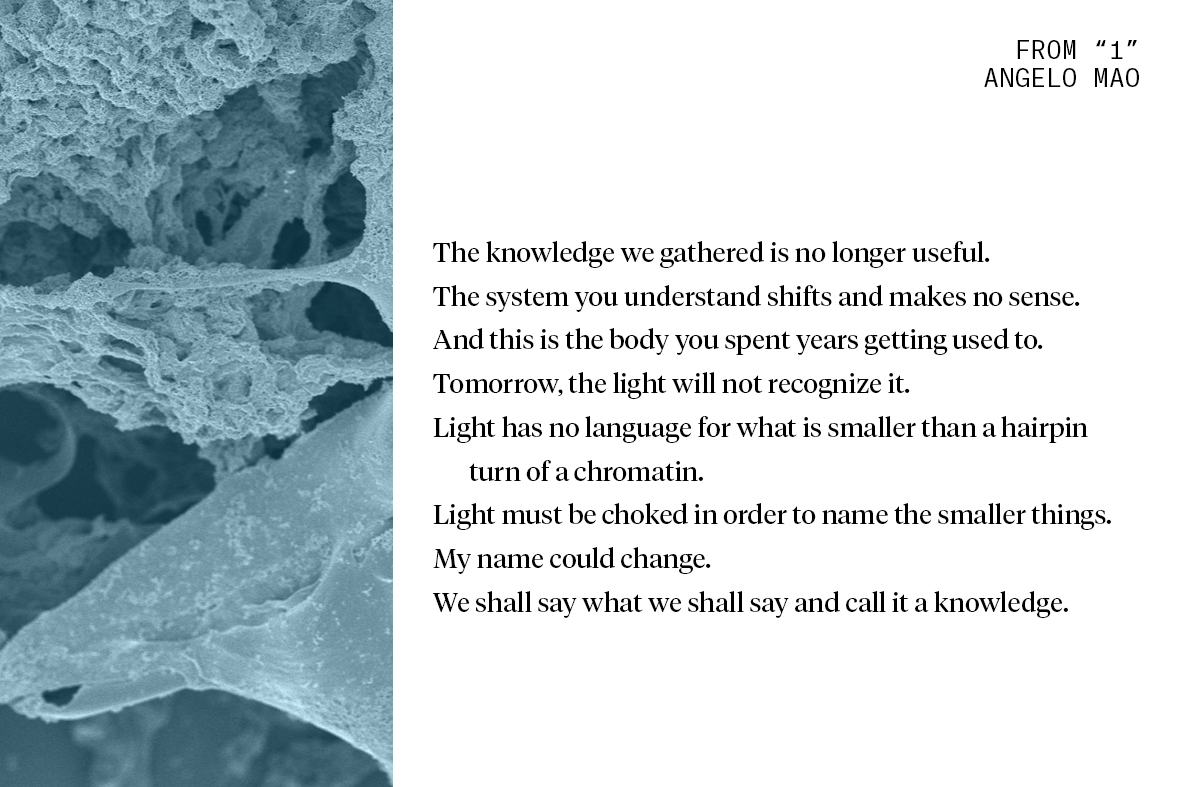

Angelo Mao found that many things he experienced while doing science did not fit into a paper. That is what inspired his first book of poetry, Abattoir, which came out last November. The book’s central themes are the experiences he had performing experiments and an aesthetic appreciation of the things he saw in the lab, like electromicroscopy or cells growing in a dish. It’s possible that many researchers take these everyday occurrences for granted, and that they may not stop to appreciate what’s right in front of them. Previously, an individual might have been dismissed as being “left-brained,” but anyone can appreciate the aesthetics in the world around them.

“Science also inspires my writing in the sense that good science embodies values that I admire and appreciate, and I see my own writing as a way to embody those values in the field of contemporary poetry,” Mao explains. “Our entire sense of reality is constantly being affected not only by scientific discoveries, but also by the kind of thinking that underpins the scientific endeavor, and I would like to see more poetry take that on as its subject.”

1/7

2/7

3/7

4/7

5/7

6/7

7/7

Further reading

Mao isn’t the only poet who has found inspiration in science. Below is a list of other science poets, curated by the Wyss’ Angelo Mao.

- A.R. Ammons

A major American poet, Ammons wrote poems strongly influenced by his training as a biologist. - Jen Bervin

Bervin’s 2017 book Silk Poems arose from a collaboration with Tufts University’s David Kaplan and Fiorenzo Omenetto; the poems were initially written in silk proteins on a silicon wafer. - Forrest Gander

In a decades-long career, Gander, who was trained as a geologist, has explored ecopoetics as means to fight climate change. - Jorie Graham

The first woman to hold the Boylton Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University, Graham has made climate change a central theme of her poetry. - Zoë Hitzig

A Harvard Ph.D. candidate in economics, Hitzig’s 2020 collection Mezzanine uses the social sciences as a lens for her poetry. - Miroslav Holub

Holub was a Czech immunologist whose career began in the fifties. His poetry, which often draws inspiration from his research, is almost a time capsule of the development of immunology as a field. - Laura Kolbe

Kolbe, a clinician, chronicles her experiences as a medical doctor in her 2021 book Little Pharma. - Jenny Qi

Qi’s 2019 book Focal Point meditates on her experiences completing her PhD in cancer research at UCSF while coping with the loss of her mother to cancer. - Sasha Stiles

Exploring the interface between humans and artificial technology, Stiles’s 2021 book Technelegy is a collaborative text between herself and Technelegy, an alter ego equipped with GPT-3 language processing.