UD English professors explain how learning to read and write poetry benefits all students

John Ernest, chair of the Department of English at the University of Delaware, wants to bring poetry to life, so sometimes he’ll start his classes with a dramatic reading of a poem.

On more than one occasion, he’s arranged for someone — usually someone with some acting experience — to come into his classroom unannounced, launch directly into a dramatic reading of a poem, and then leave. The practice, Ernest said, helps students to realize the full life of poetry specifically (and literature in general) in what otherwise is a very formal, academic setting.

“The shock of that moment and the drama of that moment sets us up for talking about the poems that we're reading in class in a different way,” Ernest said. “The students can start to hear the ways in which there's an urgency in this poetry, that this is not just an academic subject, and so that helps them to then appreciate why it is that we're taking the trouble to learn how to read literature and how to read analytically or critically.”

Being able to read, analyze and write poetry teaches students to communicate and speak on a different level, Ernest said.

“It's almost like when you're trying to tell somebody how much you love them and the language just doesn't seem adequate to account for what you're actually feeling,” he said. “Poetry hits at those moments where you need to have much more packed into what you were saying — many more levels operating at once.”

Poetry isn’t just limited to workshop classes. Indeed, poetry is a regular topic in almost all literature courses at UD, said Ernest, who will often use poetry to launch the theme of a class.

Devon Miller-Duggan, associate professor of creative writing in the Department of English, said that poetry is beneficial in areas far beyond the English classroom and in all aspects of life.

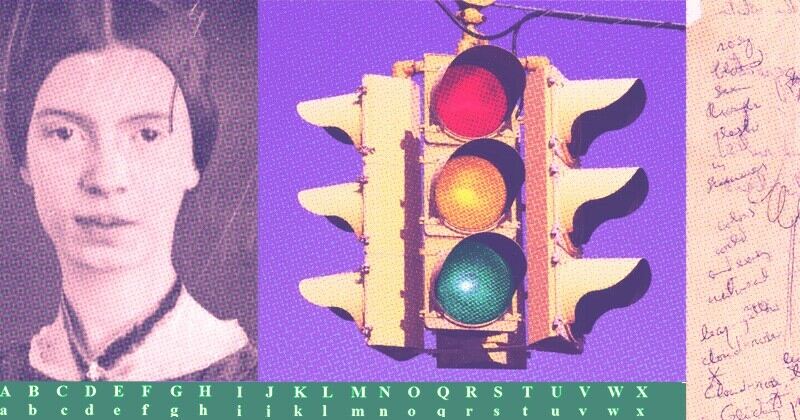

“It's about reading, and we need to read everything in life, from traffic signals to people's faces,” she said. “Being able to read poetry is the most intensive form of reading that we have in language. It is the ultimate kind of paying attention, and we don't pay enough attention in any part of our lives.”

Claire McCabe, assistant professor of English, will often have her students read poems that have social significance, including poetry that discusses racial issues, Indigenous people and the environment. She makes it a point to let students know that poetry isn’t just love poems, nursery rhymes or Shel Silverstein — although she said she loves Shel Silverstein — but that poetry goes beyond that.

“Poetry can get at something very deep, and that's what I try to show them,” McCabe said. “What being able to read poetry does is it lets the reader understand the subtleties not only of language, but of life. This particular time feels very fragile — all the unrest that we have in the world. I feel like somewhere along the line, we as a global culture have lost touch with the essence of what it means to be human, and I think poetry can bring that back.”

While writing poetry is certainly a creative process, there are many technical aspects that go into the craft, said McCabe, who is teaching a class called “Poetry Writing” in the fall of 2022. In her class, students learn about alliteration, assonance, consonance, white space, line length and more — and then, of course, put it all into practice.

“I often tell students that it's a bit like visual art — that's a metaphor that they can relate to,” McCabe said. “Just like you learn techniques when you're learning how to produce a painting, [it’s the] same thing with poetry. You might start out with an idea … but learning the craft allows them to go in and really shape it. [Poetry] isn’t something that you get an inspiration for and then you do it and there's your poem. It's something that you should conserve for a while and go back to and revise, and that's where all those craft elements come in.”

Most UD students will encounter poetry somewhere along their academic career, regardless of their major. Ernest acknowledged that not everyone will like all poems or all poets. Indeed, that’s something he embraces by bringing many different styles and different kinds of poetry to his classes. If you have enough different kinds of poems, he said, chances are students will connect with one of them.

The benefits of learning how to read and write poetry extend to non-English majors, Ernest said.

“They are sometimes some of our most enthusiastic students because after you've been using your brain to think about engineering or business for a while, many of these students absolutely welcome the opportunity to be creative and to think differently — to use their brains differently,” Ernest said. “I think they actually end up discovering that that helps them in unexpected ways when they go back to engineering or business.”

Poetry can be especially useful for science-minded students, Miller-Duggan said.

“Scientists are very linear in the way they're trained. A goes to B goes to C and you are looking for X, Y or Z outcome — it's all fairly straightforward,” Miller-Duggan said. “The problem is that the world doesn’t work that way. It's not a straight line. So giving them the opportunity to function in zigzags and leaps is ultimately going to benefit their capacity to function as scientists and to trust their instincts.”

Morgan Wright, a senior majoring in political science and English, took Miller-Duggan’s poetry writing class in the spring of 2022 and said that the best part of the class was the sense of community that was fostered. At the start of the semester, she was nervous that the workshop-heavy class would be a judgmental space, but she found just the opposite. Because of her incredibly positive experience in that class and others, she plans to pursue a master’s of fine arts (MFA) in creative writing after graduation.

Beyond teaching her the ability to write great poetry, creative writing classes at UD gave Wright insight into working with other people and collaborating.

“In a workshop setting, you have to learn very quickly that someone else's success is not your failure, and this is something I had always struggled with before,” she said. “If someone else produces something amazing, it is easy to be jealous, but it takes a lot more self awareness and confidence to step back and ask yourself what it is that makes their work so great and if that is something you'd like to challenge yourself to try to emulate with your own personal spin. I think that learning to celebrate others while also celebrating yourself is a message that is relevant in any workplace or field.”

McCabe said that when it comes down to it, poetry can help us to be more human and remind us of what really matters.

“The deep points that are made in poetry are really universal points, so poetry can be a way to erase our differences and remind us that we really are dependent on each other as a global community and even smaller communities, just as neighbors and friends,” she said. “I think it returns us to that kind of understanding rather than keeping us separate. Poetry is a way to bring people together.”