Celebrating the Blue Hen father of American study abroad

On March 11, 1919, Raymond Watson Kirkbride “arrived at the youthful age of 27,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. “I don’t feel a bit different, either.”

But oh, how the world would change because of Kirkbride’s difference.

As the University of Delaware celebrates the distinction of being the first American institution to launch study abroad a century ago, it also celebrates the pioneering spirit and enduring impact of a man born 131 years ago this month.

A World War I veteran who joined UD in 1919 as an assistant professor of French, Kirkbride sought to prevent future global conflict through cross-cultural understanding.

“He had been on the battlefields and thought, ‘We don’t want to do this again. Maybe one way we can avoid this is by priming young men for ambassadorships through international study,’ ” said Lisa Gensel, archives coordinator for UD.

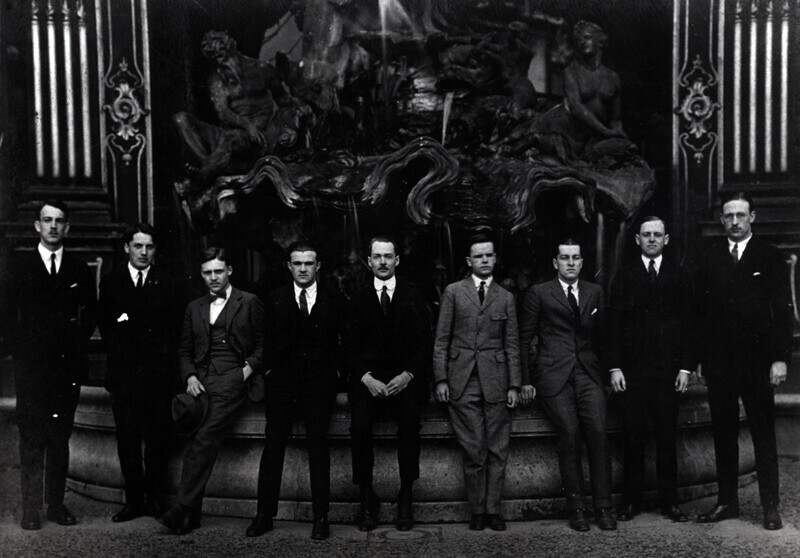

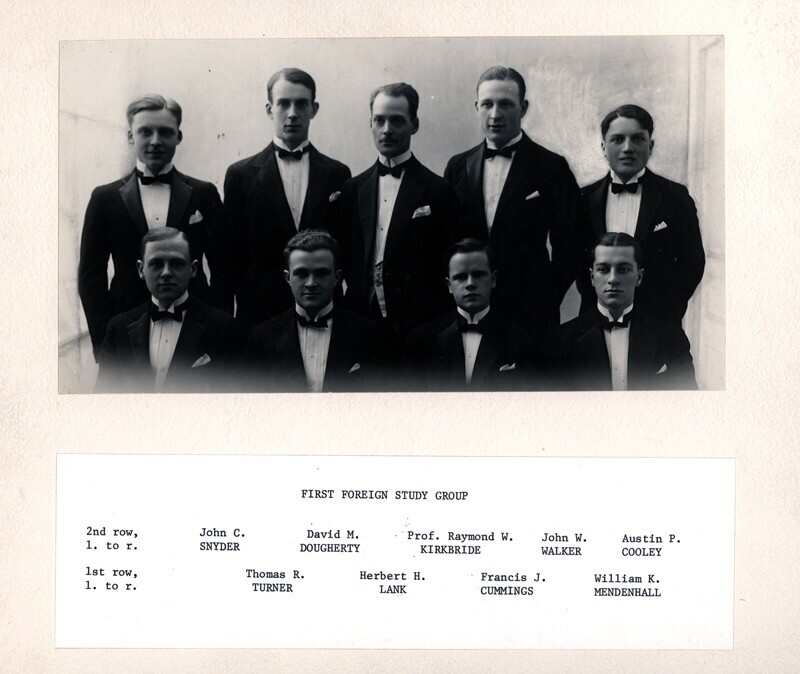

On July 7, 1923, Kirkbride and eight UD juniors set sail for France. By 1924, students from the Women’s College and other schools would join the group. In the years that followed, 127 peer institutions, including Princeton and Harvard, sent their own students on the UD experience. One described his memories as the “rosy souvenir of a nice dream,” and a particularly poetic student reporter labeled the initiative “a solid brick in the long-sought foundation of world peace.”

Of course, peace would not last, and the world would soon incur the wrath of another global conflict. But during World War II, UD’s study abroad alumni raised nearly $500 (the equivalent of about $10,000 today) to assist the Red Cross in two short weeks, reinforcing the program’s lasting humanitarian and philanthropic power.

One hundred years later, the Delaware-developed model of study abroad — in which faculty members lead academic courses and cultural excursions in foreign countries, with the noble goals of opening minds and hearts — persists.

Sadly, Kirkbride himself would see a mere fraction of his legacy unfold. On Feb. 28, 1929, just weeks shy of his 37th birthday, the Blue Hen professor died from sarcoma. A memorial library bearing his name was established in the University’s Paris headquarters, and Kirkbride was honored by the French government with their highest civilian honor, the cross of the Ordre National De La Légion D’Honneur.

At home, his legacy continues in a lecture hall built in 1976 and likely frequented by every UD student over the past 45 years. Convex like a globe, Kirkbride Lecture Hall, located at the corner of South College and Delaware avenues, evokes the architecture of another era, as if the Colosseum was built in Newark, Delaware, and enveloped in the University’s signature Georgian brick. Perhaps it’s only fitting for a man who contributed so much to the world in such a short period of time.

“His story is rather haunting,” said Elizabeth Dawson, a 2022 history graduate who served as processing archivist for UD’s Raymond Watson Kirkbride Collection. “It’s a story that didn’t get to have all of its chapters.”

And yet, the story continues. And with each passing year and every new student, it grows.